Gianni Rodari, Khachaturian y el caos que llevamos dentro

Un alegato en favor de fomentar el aprecio por las artes como forma de entender qué nos importa realmente. Y algo de IA. // A plea to foster appreciation for the arts as a way to understand what really matters to ourselves. And some AI.

(this article is written originally in my native Spanish; if you'd rather read it in English please scroll down for my own translation of my own words).

Esto no es más que una recopilación de pensamientos, una sedimentación de ideas que circulan por mi mente y que en ocasiones, como ahora, confluyen y forman una amalgama más ordenada que de costumbre y desde luego con mucha más estructura que lo que suelo manejar en mi día a día. Así que, lector atento y muy apreciado por quien escribe, no espere ninguna gran revelación ni tampoco un aprendizaje cierto. Esta amalgama es tan sólo una historia personal, con un subtexto que se intuye en su transcurso pero que no termina de salir a flote. Quizá a usted le haga aflorar algo.

Empecemos. Supongamos dos textos breves:

A

un árbol, un árbol rojo, un árbol rosa

pájaros, flores y una mariposa.

B

el señor y la señora pato

tomaban té con un zapato.

Como estaba de maravilla,

decidieron llamar a una zapatilla.

La zapatilla corrió emocionada,

y chocó con una bicicleta que salió disparada.

La bicicleta atravesó la merienda

y recorrió la ciudad llevando en sus riendas

a los dos patos con té en sus tazas delicadas,

al zapato asustado y a la zapatilla atontada.

Esta suerte de versos breves, infantiles y con cierto aire a Gloria Fuertes surgen en el siguiente contexto: íbamos mis niñas y yo en el coche al colegio, y para amenizar el viaje les conté la historia B, (historia que me vino a la cabeza una mañana recién levantado), y les pedí que la continuaran. Lo hicieron con una imaginación limitada por las horas tempranas, y algo sesgada por el tipo de historias que han consumido en su corta vida. Para ampliar el abanico de su capacidad creadora, les propuse otro juego: mirad por la ventana y decidme dos cosas para que montemos una historia nueva. Mi hija mayor, 6 años, propuso: "pájaros y flores. Y también mariposas", la menor, 4 años: "un árbol, un árbol rojo, un árbol rosa" (no había árboles rosas, ni tampoco mariposas visibles, pero es aquí donde se empieza a fomentar la creación y es perfecto que empezaran añadiendo elementos desde el principio del juego). Junté lo que dijeron y salió una pequeña poesía, el texto A con el que empieza este confuso relato.

En casa, más tarde, les propuse que dibujáramos esa pequeña poesía. Que dibujaran ellas y que le pidiéramos a vqgan+clip que lo dibujara. Vqgan y clip son dos modelos de inteligencia artificial, uno de ellos es capaz de crear imágenes sintéticas y el otro es capaz de traducir lenguaje humano a lo que el otro necesita para crear una imagen. En conjunto, toman una frase que le proporcione usted y le brindan una imagen que trata de representar lo que ha tenido usted a bien formular. Total, que el texto A, simplificado (un árbol rosa, flores y mariposas), se lo dí a la máquina para que ejercitara su propia imaginación (¿tiene imaginación?). Las dos imágenes que pueden ustedes ver aquí abajo son el resultado tras 50 y 250 intentos (la máquina se pone a dibujar, y en cada paso evalúa, por entendernos, si se parece a lo que le hemos pedido, y sigue refinando el resultado hasta que uno la pare). Enseñé la imagen a las niñas, pero ya estaban cansadas y no les pareció demasiado revolucionario que le pudieras pedir a un portátil que te dibuje algo. Estas nuevas generaciones...

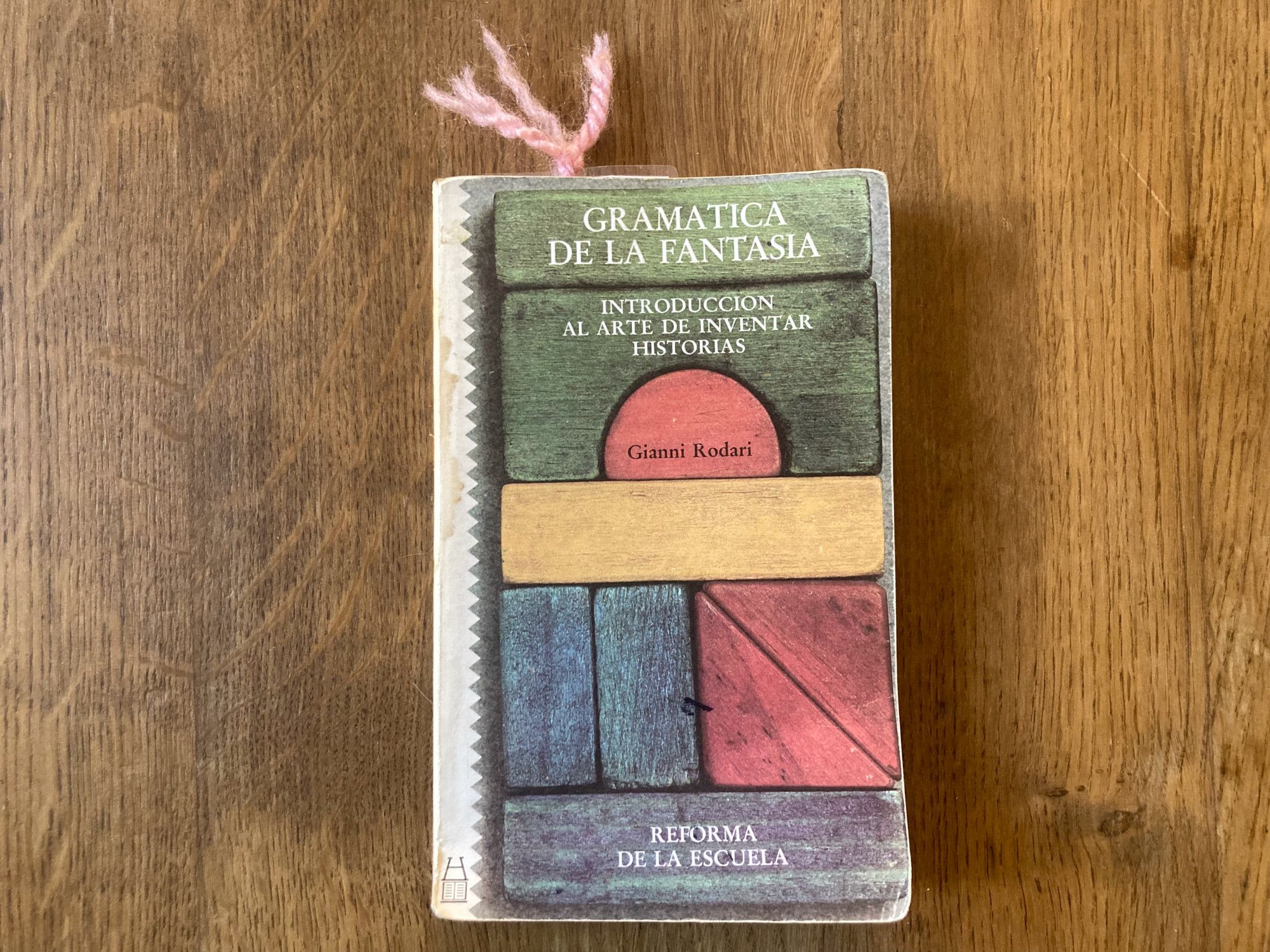

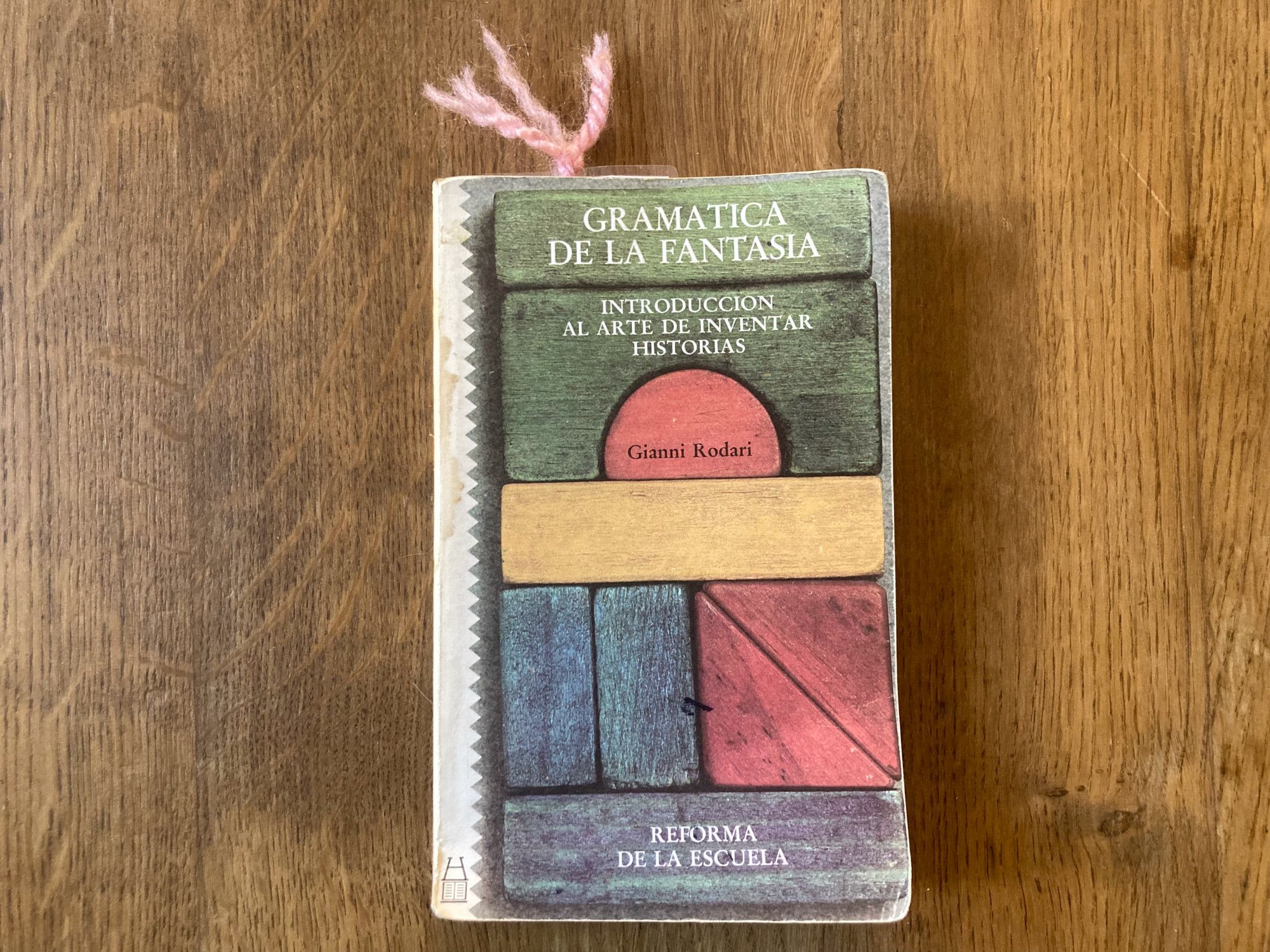

El caso es que estoy leyendo un libro que me encanta, "Gramática de la fantasía", de Gianni Rodari. Me lo dió para leer una tía mía, hermana de mi padre y décima de once hermanos, alguien que tiene sinestesias visuales y que llevaba tiempo, según me cuenta mi padre, recomendando el libro a todo el mundo a ver si alguien lo aprovechaba. Me lo hizo llegar a mí (¡gracias Fátima!), y me encantó y fascinó nada más verlo: su portada (edición de 1976, editada por Reforma de la Escuela), sus páginas envejecidas, el subtítulo: "introducción al arte de inventar historias". El libro hace una exposición de técnicas, juegos y otros para estimular la imaginación y la narración fantástica en los niños (niños de todas las edades, entre los que me incluyo). En esta época de hipertecnificación, consumo rápido y satisfacción instantánea no podía tener mayor atractivo un objeto que promete una alternativa en sí mismo y que presenta mecanismos para luchar contra la normalización del pensamiento (¿qué hay más útil que esto?).

Yo no conocía a este autor (no conozco casi nada). Hoy, tras el pequeño juego con mis hijas, decidí investigar un poco más. Leo con interés y mucha alegría que es considerado el mejor autor infantil italiano del siglo xx (con alegría por él, me alegra realmente que alguien que escribe tan bien ese libro que tanto me llena y estimula tenga un gran reconocimiento). No sólo eso: leo acerca de una de sus obras, Il romanzo di Cipollino (Las aventuras de Cebollino), donde el niño-cebolla Cipollino lucha contra el trato injusto de sus compatriotas por parte de la realeza (el Príncipe Limón y el malvado Caballero Tomate) (descripción extraída tal cual de Wikipedia), una obra que supone una crítica a la opresión, el totalitarismo, las desiguladades y las injusticias. Tuvo gran repercusión en la Unión Soviética, y me parece estupendo que se le dieran determinados honores como editar una serie de sellos con el personaje, o que fuera convertida en ballet por Karen Khachaturian (Կարեն Խաչատրյան, o Карэн Суренович Хачатурян si así lo prefieren ustedes) en 1973.

Me encanta que alguien decida tomar un texto infantil y lo convierta en un ballet. Me encanta que sea Khachaturian y que fuera en 1973. Karen es sobrino de Aram Khachaturian (Արամ Խաչատրյան, o Арам Ильич Хачатурян), compositor de sobra conocido, si no por nombre seguro que sí por piezas como su Danza del sable, de su ballet Gayane, o por su ballet Espartaco. Mi primer contacto con su obra fue, como quizá para otros, precisamente a través de la Danza del sable. La escuché en una escena mítica de una película mítica del mítico Billy Wilder, One Two Three (Uno Dos Tres, en su título en Español), cuando era yo el niño y veíamos películas antiguas con mis padres en casa. Uno Dos Tres, en concreto, es de mis favoritas de aquella época, una mezcla de película bien ejecutada, historia con trasfondo, sentido del humor afinado y carcajada limpia (durante muchos años casi perdía la respiración por la risa que me daba cuando llegaba la escena de la Danza del sable, precisamente; es posible que me riera tanto por la escena como por la risa contagiosa de mi padre). Siempre he sentido una conexión con mis padres que se mueve en un plano de una cultura a la que no soy capaz de llegar por el momento (o sencillamente es diferente a la mía y a mis tiempos), y más en detalle la conexión con mi padre existe en un plano de ese humor relativamente sofisticado y elegante, de lo inesperado sin recurrir a lo histriónico, que también manejaba Billy Wilder. Mi tía, la que me hizo llegar el libro, es uno de los exponentes más descontrolados, incluso, de esa capacidad creativa que hace a mi padre y sus hermanos salirse de lo común para contar una historia inesperada, una anécdota desternillante, para colocarse en un paralelo del mundo mundano y abrir una puerta a otro lugar donde habitan tantos recuerdos míos, felices todos estos, de infancia. El hilo conductor de este relato que escribo no es evidente hasta el momento, creo que no al menos para cualquier cuerpo ajeno al mío, pero yo veo una relación entre todo esto que me resulta curiosa e interesante.

Que Cipollino la compusiera el sobrino de Aram Khachaturian en 1973 me resulta también una coincidencia intrascendente pero entretenida por lo siguiente: desde que nació mi primer sobrino, hijo de mi hermano, nacido en 1973, y durante su primer año de vida tuve la costumbre de o bien tararearle alguna pieza de música clásica o bien directamente reproducir alguna pieza que me pareciera que acompañara bien la ocasión. Recién nacido, en el hospital, la tarareé el Concierto de Brandenburgo número 3 de Johann Sebastian Bach (espero que algún día sepan perdonarme, tanto mi sobrino como Johann Sebastian, por mi pobre interpretación). Cuando contaba con apenas unos meses, en una visita a su casa, tomé a mi sobrino en brazos y bailé con él al son del vals de la Suite Masquerade, de Aram Khachaturian. Es todo un tanto disperso, pero confluyen en este relato sobrinos, el año 1973, Khachaturian, niños, un ballet infantil, un autor que me mueve a proponer juegos a mis hijas. Seguramente no sea nada, pero a mí me hace ilusión. Aunque lo más probable es que sólo sea una excusa para sacar recuerdos de mi hermano, o para maravillarme voluntariamente con la belleza que se esconde en estos rincones de la existencia que transitamos sin apenas saber qué, cómo, cuándo, dónde, por qué. O, en realidad, es una forma de expresar que nuestro día a día está repleto de circunstancias que nos llaman la atención y nos movilizan en nuestro fuero interno porque nuestra mera existencia es una colección de recuerdos conectados entre sí, que nos dan un sentido y que explican en gran medida quiénes somos y por qué reaccionamos como lo hacemos. Una forma de expresar que tenemos una base emocional que en realidad no podemos comprender en un momento dado en su totalidad, pero que nos guía.

En este sentido, me parece elegante que todo lo que acontece en esta historia es expresión. Una narración que surge de unas niñas un tanto adormiladas en medio del tráfico de la mañana camino del colegio, un libro escrito por un creador de historias, la música de fuerte carga narrativa de los Khachaturian, la música eterna y universal de Bach, bailar con tu sobrino, acordarte de un ser querido. Todo es expresión pura, ¿expresión de qué? Expresión de emociones. Todo lo que expresamos tiene un apoyo en alguna emoción. No podemos no reaccionar, y por tanto no podemos no tener una emoción. Y esas emociones, intangibles por completo, inmateriales como ninguna otra cosa en el mundo, tienen la misma fuerza que lo más absoluto, tangible y concreto de la naturaleza. Se abren paso a través del tiempo, a través de los idiomas, los recuerdos, de la novedad, de los recursos expresivos. Cuando el lenguaje verbal no llega, está la danza. Cuando la abstracción es total, está la música. Las artes plásticas comunican concreciones formales o abstractas, la letra escrita provoca con imprecisiones deliberadas, abre puertas con giros inesperados en lugares insospechados.

En esta época donde hablamos con frecuencia de impulsar la educación en ciencia, tecnología, matemáticas e ingeniería (énfasis que comparto), me parece igualmente interesante y necesario que entendamos que el puente entre nosotros y lo que quiera que hagamos con todos esos avances sigue siendo uno construido por expresión de base emocional. Y aún diría más: es el puente entre cada uno de nosotros (y nuestras circunstancias), por mucho avance que creemos. Porque nuestra base es esa: no podemos comunicarnos con otros entes sin como mínimo saber que procesamos nuestra vida desde las emociones. Estamos construyendo inteligencias artificiales que algún día tendrán su propio comportamiento, sus neuras, sus sueños, su propia versión del buen y mal humor. Todo lo que hagamos para crear una buena capacidad de expresión entre esos nuevos seres y nosotros es un esfuerzo bien invertido. Todo lo que hagamos para poder expresarnos bien entre nosotros es un esfuerzo bien invertido. Las diversas formas de expresión que tenemos a nuestro alcance nos permiten precisamente eso, y nos habilitan para explorar todas estas relaciones, existentes o nuevas, en toda su dimensión. Dimensión que existe y que nos influye y condiciona, por mucho que en un momento dado no la tengamos presente de una manera consciente. Otro pensamiento relacionado: en el camino hacia la construcción de sistemas de inteligencia artificial más complejos y más útiles en su simbiosis con el ser humano, es interesante investigar la posibilidad de que estos seres creados por nosotros puedan entender también que el humano tiene una base emocional (en general, en todo animal). Que les podamos enseñar qué son los sentimientos, y que en algún momento, cuando ellos desarrollen los suyos propios, entendamos nosotros cómo son.

«El uso total de la palabra para todos» me parece un buen lema, de bello sonido democrático. No para que todos sean artistas, sino para que nadie sea esclavo.

Gianni Rodari finaliza el prefacio de su libro con una frase que se me antoja fundamental para nuestra especie. En su traducción al español de la edición de los 70 que tengo entre mis manos dice: "«El uso total de la palabra para todos» me parece un buen lema, de bello sonido democrático. No para que todos sean artistas, sino para que nadie sea esclavo". Me maravilla. Me atrevo a extender el sentido un poco más allá de la palabra: el uso total de las artes para todos, o por lo menos la sensibilidad para apreciarlas es precisa para que conectemos con lo que nos mueve. No para que todos seamos artistas, sino para que ninguno seamos esclavo.

(and now my own translation, which will probably be devoid of some nuances of the original text & its emotions, but I hope I can transmit the message that lies therein in a useful way for you, dear reader).

This is just a recollection of thoughts, a sedimentation of ideas that circulate around my mind and that oftentimes, like in this occasion, converge to shape an amalgam that exhibits a higher order than usual, and surely with a more defined structure than what I operate with in my day to day. So, attentive and dear reader, do not expect any high revelation or any certain learning. This amalgam is just a personal story, with a subtext that permeates throughout but never dares to come afloat. Perhaps it blossoms something in you.

Let's start. Let us suppose two brief texts (these make sense in Spanish, with their rhymes and all, I am just transposing a literal translation here):

A

a tree, a red tree, a pink tree

birds, flowers and a butterfly.

B

mister and miss duck

had tea with a shoe.

since they found it to be very pleasing

they chose to call in a slipper;

the slipper ran excited for the occasion,

and hit a bicycle that flew off promptly.

The bicycle crossed the afternoon tea

and rode the city carrying along on its reins

the two ducks with tea in their delicate cups,

the startled shoe and the stunned slipper.

These brief verses, infantile and with a certain flair of Gloria Fuertes (a renowned Spanish poet with ample literary production for children of all ages) come up in the following context: my little girls and I were on our morning car ride to school, and to make the trip more interesting I told them the story B (a story that appeared on my head one morning as I woke up), and asked them to continue the story. They did so with an imagination somewhat limited by the early hours, and biased towards the type of stories they have been exposed to in their short lives. To broaden the scope of their creating capacity, I proposed a second game: look out the window, tell me two things you see and we'll make a story with that. My oldest girl, 6 years old, said: "birds and flowers. And also butterflies". The smallest, 4 years old, added: "a tree, a red tree, a pink tree" (there were no pink trees nor butterflies in sight, but creativity and imagination start here and it is just perfect that they chose to add a little something right at the start). I put together what they said and a little poem emerged, text A with which this confused story starts.

Later, at home, I proposed that we could draw that little poem. They would do their version, and we would ask vqgan+clip to draw it as well. Vqgan and clip are artificial intelligence models, one of them creates synthetic images and the other translates human language to the type of input needed for its companion model to produce an image. Together, they take a phrase you offer them in human language and get back to you with an image that tries to represent it. So I gave text A (simplified: "a pink tree, flowers and butterflies") to the machine so it would exercise its own imagination (will it ever have one? does it already have one?). The two images you can see down here are the result after 50 and 250 iterations (the machine produces an image each iteration and sort of evaluates if it looks like what we asked for, and keeps going until we ask it to stop). I showed the image to the little girls, but they were too tired to admire the fact that you can ask the laptop to actually draw something. These new generations...

Anyway, I am reading a book that I love so far, "Grammar of Fantasy" by Gianni Rodari. It was sent to me by an aunt of mine, my father's younger sister, the tenth of eleven brothers, someone who has visual synesthesias and who had been recommending the book for a long time, according to my father, to everyone in an attempt to expand the reach of its message. She made sure it came to my hands in particular (thanks so much Fátima!), and I was fascinated the moment I saw it: its book cover (from the 1976 edition she gave me, edited by Reforma de la Escuela), its aged pages, the subtitle "Introduction to the art of telling stories". The book is an exposition of techniques, games and others to stimulate imagination, fantasy and narration in children (children of all ages, among which I count myself in). In this age of hypertecnification, fast consumption and immediate gratification, I couldn't find a greater attraction towards this object that promises an alternative in itself and that proposes mechanisms to fight against the normalization of thought (is there anything more useful than this?).

I didn't know this author (I barely know anything). So after this little game with my girls I went to research a bit more. I read with interest and much happiness that he is considered to be the greatest Italian child author of the 20th century (I'm happy for him, or for his memory, as I really am glad to see that there is a recognition for someone who writes such an interesting and well written book). Not only that, I come to know about one of his works, Il romanzo di Cipollino (The Adventures of Little Onion), where the kid-onion Cipollino fights against the unfair treatment of his compatriots in the hands of the royalty (Prince Lemon and the mean Lord Tomato) (description taken from Wikipedia). A work orchestrated as criticism towards oppression, totalitarism, inequalities and injustice. It had a great repercussion in the Soviet Union, and I find it wonderful that it was the subject of certain honours such as having a series of stamped made after the character, or that it was turned into a ballet by Karen Khachaturian (Կարեն Խաչատրյան, or Карэн Суренович Хачатурян if you so prefer) en 1973.

I love that someone takes a children's literary piece and makes a ballet out of it. I love that it is Khachaturian and that he did so in 1973. Karen is the nephew of Aram Khachaturian (Արամ Խաչատրյան, or Арам Ильич Хачатурян), renowned composer; if you don't know him by name you surely have listened to some of his works, such as the Sabre Dance from the ballet Gayane, or his ballet Spartacus. My first contact with his work was, as it may have been the case for others as well, through the Sabre Dance. I listened to it as part of a mythical scene of a mythical movie by the myth of Billy Wilder, One Two Three, when I was a little kid and we watched classical movies with my parents at home. One Two Three, in particular, is one of my favourite movies from those times, a mix of a well executed and round movie, a story with a solid background and message, a fine sense of humour and clean laughter (for many years I nearly choked laughing with the Sabre Dance scene, precisely; probably both for its own hilarious nature as well as the contagious nature of my father's laugh). I've always felt a connection to my parents that moves on a cultural plane that I cannot yet reach (or is just different to mine and my time). More in detail, the connection with my father exists in a plane of that refined sense of humour, elegant and sophisticated, a humour of the unexpected without resorting to histrionics, a humour which Billy Wilder also mastered. My aunt, the one who had the book land in my hands, is one of the largest exponents, even sometimes out of control, of this creative capacity that my father and his brothers and sisters have to step out of the common to tell an unanticipated story, a hilarious anecdote, to position their counterparts in a parallel to the mundane and open a door where so many memories of childhood of mine inhabit, all of them of a happy nature. The main argument in this story that I write is so far not evident, not at least for those who inhabit a life different to mine, but I see a connection throughout that I find amusing and interesting.

The fact that the Cipollino ballet was composed by the nephew of Aram Khachaturian in 1973 is another fertile ground for my mind to spend some time pondering coincidences. Ever since my own first nephew was born, the first son of my brother, who was born on 1973, during his first year of life I had the habit of either humming some classical music piece to him or outright play some pieces that I found uplifting for the occasion. As a newborn baby, at the hospital, I whispered in his ear the starting bars of the Brandenburg Concert num. 3, by Johann Sebastian Bach (I hope someday they both can forgive me, my nephew and Johann Sebastian, for my poor performance). When he was just some months old, in a visit to his house, I played the waltz of the Masquerade Suite , by Aram Khachaturian (composed in 1941, the year my father was born) and danced with him in my arms around the room. Ok, this is all a bit loose, but this story connects many vital story points from a book I am reading now, the games it prompts me to have with my girls, the games I did with my nephew, 1973, the Khachaturians. Probably I am just looking for an excuse to bring out some memories from my brother, or to voluntarily marvel at the beauty that hides in these corners of the existence we circulate without almost knowing what, how, when, where, why. Or, maybe, it's me trying to say that our everyday is full of circumstances that catch our attention and movilize our inner workings because our mere existence is a collection of memories connected and intertwined, which give a meaning to our selves and greatly explain who we are and why we react to things the way we do. A manner of saying that we have an emotional base that we cannot truly comprehend in a given moment in its entirety, but that guides us.

In this sense, I find it elegant that all that happens throughout this little narration is a way of expression. An account of ideas, thoughts and reflections that emerges from two little somewhat dozy girls in the middle of morning commute traffic on their way to school, a book written by a creator of stories, the music charged with a strong narrative character of the Khachaturians, the eternal and universal music of Bach, dancing with your newborn nephew, remembering a loved one. It all is pure expression. Expression of what? Expression of emotions. Everything we express is supported in some emotion. We cannot not react, and therefore we cannot not have an emotion. These emotions, completely intangible, immaterial like nothing else in this world, have the same strength as the most absolute, tangible and particular of nature. They find their way through time, languages, memories, novelty, expressive resources. When verbal language is not enough, there's dance. When abstraction is total, there's music. Plastic arts communicate formal concretions or abstractions, written word provokes with deliberate imprecisions, and opens doors with unexpected turns in unsuspected places.

In these times when we typically talk about fostering education in science, technology, mathematics and engineering (an emphasis that I agree with), I find equally interesting and necessary that we understand that the bridge between us and whatever we create with all the advances we create with the STEM disciplines is still built upon an expression of an emotional nature. I would say even more: it's the bridge between each and every one of us (and our circumstances), no matter the advances we create. Be cause our nature is that one: we can't communicate with other entities without acknowledging that we process our life from our emotions. We are currently building artificial intelligences that will some day have their own behaviour, their crazes, dreams, their own version of good and bad mood. Everything we may do towards nurturing a healthy means of expression between these beings and us humans is a good invested effort. Everything we may do to nurture a healthy means of expression among ourselves humans is a good invested effort. The diverse means of expression we have at hand allow us to do precisely that, and enable us to explore all these relations, new or existing, in all their dimension. Dimension that exists, influences and conditions us, no matter how conscious we are of it in any given moment. Another related thought: in the way towards the construction of building more complex AI systems, and more useful in their simbiosis with us humans, it's interesting to research the possibility that these artificial entities may also understand that we have an emotional nature. That we may teach them what feelings are, and that we understand their own version of feelings whenever they arise.

«The total use of words for everyone» seems to me like a good motto, with a beautiful democratic sound. Not for everyone to be an artist, but for no one to be a slave

Gianni Rodari ends the preface of his book with a phrase that I find fundamental to our species. My translation to English of the Spanish translation of the edition from the 70s that I have in my hands goes like this: "«The total use of words for everyone» seems to me like a good motto, with a beautiful democratic sound. Not for everyone to be an artist, but for no one to be a slave". This marvels me without limits. I dare extend the meaning of this beyond the use of words: the total use of arts for everyone, or at least the sensibility to appreciate the arts is essential for each of us to connect with what moves us. Not for everyone to be an artist, but for no one to be a slave.